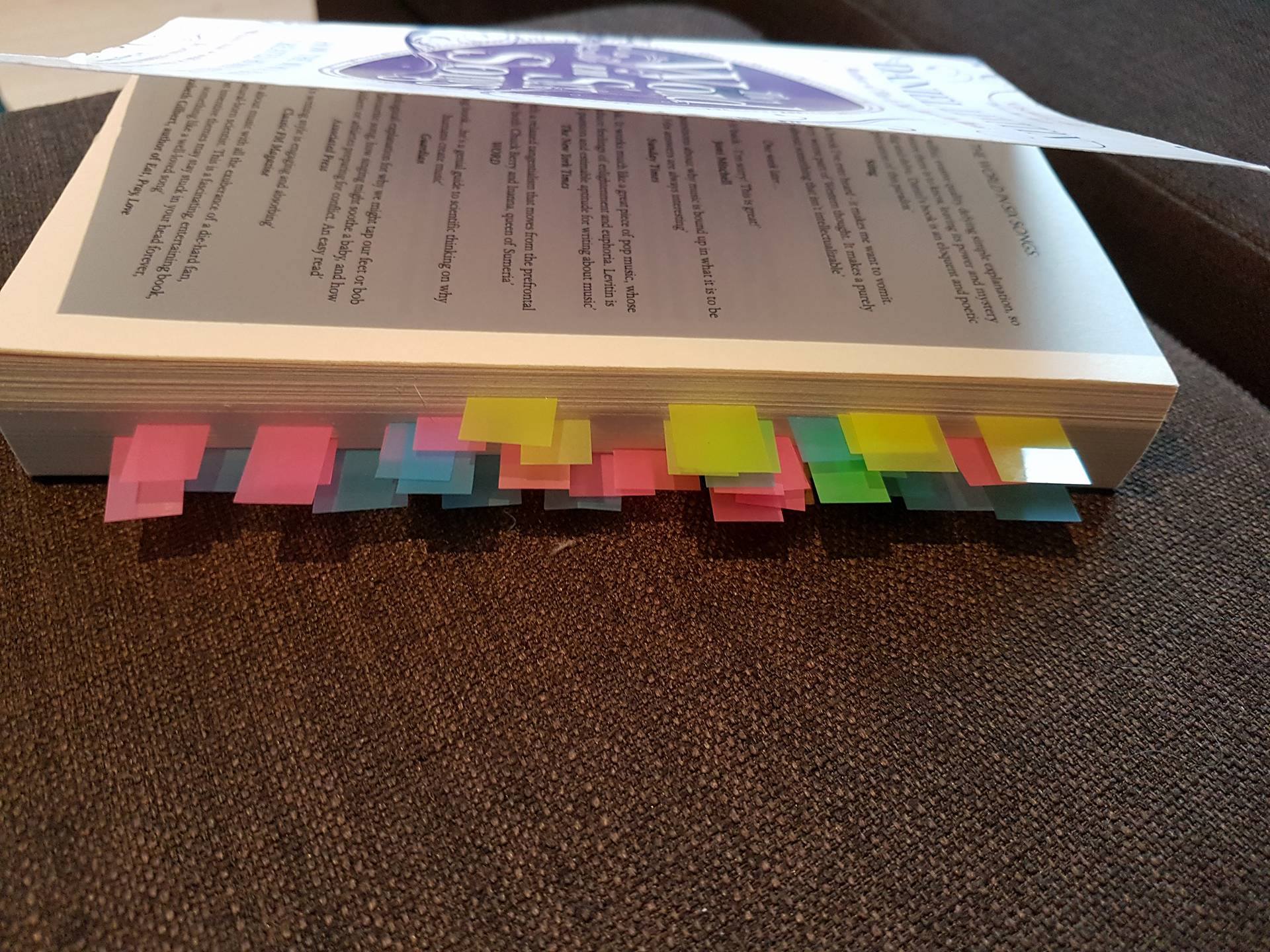

One of the most known books tackling music science is Daniel Levitin’s 2009 book The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature. It was also one of the first books I read when I started to get interested in the topic. This means that for the past year or so, my copy of the book has looked like this:

When reading, I use post-its to mark things I find interesting.

Unlike what its title suggests, the book doesn’t actually make a playlist of six songs that can describe the world. Instead Levitin describes it in terms of what music does for us humans. He divides songs into those of friendship, joy, comfort, knowledge, religion, and love. Songs of friendship refer to the role of music in promoting social bonding, songs of joy tackle the beneficial effects of music, and the chapter of songs of comfort tells us why sad music is good for us when we’re feeling down. Further, songs of knowledge talk about how music is used to transmit information, songs of religion describes the use of music for ritual purposes, and songs of love … well, that’s pretty self-explanatory.

However, like always, I will not try to make a comprehensive book review but will rather list a random assortment of things I learned from the book that I found fascinating. Without further ado, here they are:

Sing out loud! You can feel better if you rock around singing out loud in your living room because it releases endorphins. Scientists don’t know why that is, and that makes them feel rather uncomfortable. They think they should know everything. Well, tough.

Music therapy probably works but it’s really difficult to figure out the right things to measure. While it’s clear that music can help people, it’s unclear what is happening to the group that is not getting music. Still, there have been studies that show that music can change our brains and we can feel better, be under less stress, our immune system can strengthen … I personally am a very strong proponent of music therapy and have nothing but respect for the profession.

Anticipation is crucial for music. Levitin talks about TRIP – tension, reaction, imagination, and prediction as being in the center of listening to music. The cycle of tension and release is what makes music enjoyable.

Sad music cheers us up. When we cry because we’re sad, our tears contain prolactin, which is a tranquilizing hormone. It’s possible that sad music helps us because it tricks our brain and makes it release prolactin. Consequently, our mood is improved.

You can’t fake music. It’s easy to fake sincerity in language and nearly impossible to fake it in music. This is why some claim that music might have older origins than language – for survival, truth is necessary.

We have music in our nature, which is something I’ve already mentioned before, but it is still fascinating to me. When looking at interactions between mothers and children of different cultures, we can see similarities between them in that they are largely musical.

Music transfers knowledge over time, but broad outlines of the song’s story are remembered rather than every individual word. That explains folk tradition and how we still know songs that were sung hundreds of years ago. Additionally, while we can’t recall texts very well, we are brilliant at remembering song lyrics. This is also partially due to the fact that songs often use cliched expressions that we already know.

Two awesome researchers decided to mess with singers. They removed certain “poetic” words from songs, exchanged them with different (“uglier”) words, and asked singers to remember this second version. Using reconstructive memory, when the singers sang back the songs, they used the original poetic words rather than the changed version.

You have rhythm in your body. When you sing your favorite songs, you usually miss the pitch, but you catch the perfect tempo. And if you forget a couple of words in the middle, you continue singing at the next appropriate moment, as if a band was actually playing and you had instrumental music in your background.

English speakers often rely on the alphabet song when trying to recall the next word in the alphabet. Because the song is chunked (abcd efg hijk lmnop qrs tuv wxyz) it is easier for people to remember what comes before g than what comes before h. Crossing the boundaries just takes longer.

The singing soldiers: in the military, they learn certain tasks using songs. A song teaches them to synchronize motor actions of assembling as well as tunes different participants.

Children are computer machines. They learn both language and music using complex calculations of how probable it is that a sound, word or note is going to appear. Shame that we don’t keep this probabilistic knowledge for later …

The musical brain has three cognitive components: perspective-taking, representation, rearrangement. That means we can think about our own thoughts, we can think about things that aren’t currently happening, and we can combine objects in different ways and put them into different categories.

Animals don’t have music, sorry. While bird song or whale song sound musical to us, they are simply communication to them. Rather disappointing, really.

But that’s science for you. The more I read, the more interesting things I find out but I also discover that certain things just aren’t true. Like animal songs. Or the bilingual advantage. But that’s what makes it so much fun.

Soundtrack: The Killers – All these things that I’ve done

Disclaimer: These are book thoughts on The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature (2009) by Daniel Levitin. The content is the author’s intellectual property.