And we can’t live without it

I feel lucky, sometimes, because I’ve chosen to focus my academic efforts on a field that arouses interest in both the general audience and amongst scientists. Consequently, there are books which are perfect for a relative beginner such as myself: books that talk about the scientific aspects of music in an understandable way. One such book is Philip Ball’s The Music Instinct: How Music Works and Why We Can’t Do Without It (2010). Below are a couple of curiosities I learned while reading it.*

*When I say curiosities, that means the book is full of sticky notes of different colours. I’ve wanted for a while to develop a colour-coding system but unfortunately I always end up just choosing the sticky note that feels like the right one at the moment.

The Music Instinct combines several scientific disciplines, from psychology to mathematics, to try to get to the bottom of why music moves human beings so deeply and always has. It’s easy to read and has 13 chapters that are curiously named after different musical terms, aptly beginning with a Prelude and ending with a Coda. The book itself covers a variety of topics and, most importantly, cultures. This is one of the things I like about the field: in recent years, authors have been going out of their way to include non-Western music cultures, as they should. As Ball explains in the book, the neglect was often there because it is easier to test music perception on industrialized cultures than it is on tribal societies. But on the other hand, if we wish to learn about why human beings make music, studying tribal music (used for ritual and dance) undoubtedly tells us a lot more.

So, without further ado, here are some interesting facts.

Some African cultures use “talking drums” as a sort of Morse code. By playing an instrument such as xylophone, they can convey information, even to the extent where the musician is able to make a joke on someone’s extent that is entirely understood by the listeners. A reason for this is the tonality of African languages and its pitch structure.

It has been speculated that making music is sexy, from an evolutionary point of view, because it “displays coordination, determination, good hearing, and perhaps stamina” (Ball, 2010, p. 20). Music thus signals good genes and could be there for reproductive purposes.

There are those (including myself) who think that there used to exist a “musilanguage” from which music and language developed. A point in favour of this view is the fact that music and language share some structural properties, namely that they both use rules to combine basic acoustic blocks and create meaning, and that they use pitch and rhythm.

Newton’s hair was so big because it was hiding his love for music.

Scientists have always been fascinated by music! Newton was convinced that colour and sound must be related, and he proposed his seven divisions of the rainbow because the (Western) musical scale has seven notes. Isn’t that cool?

Mathematicians are important for music. Deciding how to tune the piano has long been debated and the equal temperament system is popular, but still problematic. If we wish to have equal distance between 12 semi-tone steps, the frequencies have to be be multiplied by 21/12, which is an irrational number. Mathematicians like the number and find it elegant, others … less so.

Our brain is magic. It can identify two different sets of harmonics, even if the two notes are played at exactly the same time. … But it’s not that magic. If a song is played and only one note is substituted for the same note but an octave higher, it is difficult (if not impossible) to recognize the melody. On the other hand, if the entire melody is transposed one octave higher, there are no problems whatsoever.

Babies are music connoisseurs. Infants, between 6 to 9 months of age, already learn to prefer a certain sort of scale. That means that a French baby, for example, would already at that age find music in Indian raga scales puzzling.

High is low and low is high. It is obvious to us now that we call notes high when they have a greater frequency. That wasn’t always the case. The ancient Greeks called notes that were higher in pitch “low”, simply because they were played lower on the strings of the kithara.

Learning by chunking. Like in language, we also use chunking strategies in music, remembering bars rather than notes. If you’re a musician, you surely had the experience of the following dialogue. “Can you play from this note?” Answer: “Can I play from the beginning of the line?”

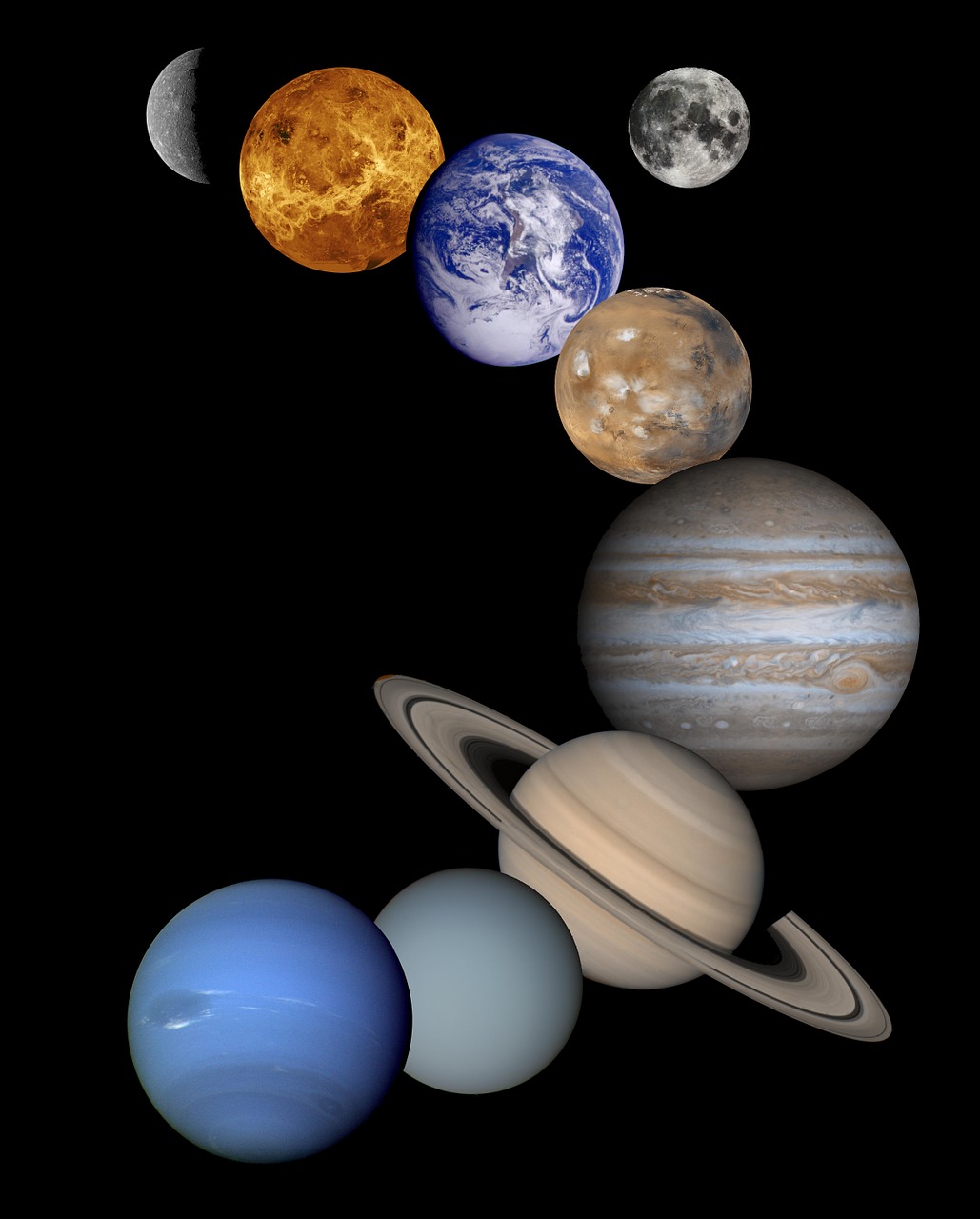

Celestial harmony of the planets.

Can you connect music with aliens? Yes, yes you can. Kepler wrote a book “Harmony of the World”, in which he claimed the planets were singing a celestial harmony. Each planet had a different vocal range. I so hope that’s true.

We have music in our brains. Major and minor keys (“harmonic space”) are, neurologically speaking, literally imprinted on a musician’s brain, projected onto the brain tissue.

Nobody knows what makes timbre so special. A musician can distinguish between instruments’ timbre (or “voice”) and, I have personal experience with this, a violin professor can play three notes on your violin and know you haven’t practiced. But science doesn’t know why. Yet.

We learn musical associations, which is why we have a hard time processing “foreign” music. Some Javanese music expresses great happiness, but Westerners will think it’s sad, because of the presence of the minor third. However, it is often the case across cultures that higher pitches mean happiness.

You don’t know what you want. If you want to be satisfied with your listening experience, the music has to thwart your expectations a bit. That’s why The Beatles became so popular – they changed the usual melody just slightly.

Musical nostalgia is normal. If you are above 25 and hear yourself saying “Ugh, this modern music, I miss the good old days”, there is a good reason for that. We tend to prefer and have strong emotional responses to music we listened to between 15 and 25 years of age.

Language can definitely influence music! Looking at English and French composers of 19th and 20th century, researchers discovered that the rhythm and melody of the language are reflected in the music.

Maybe we need musical copyeditors too. If you hear a wrong chord in a harmonic sequence, the same parts of your brain activate as when you hear a grammatically wrong sentence. Scientists aren’t quite sure what that means yet.

And it is exactly this that seems to characterize the field of music cognition: scientists can suddenly explore the brain in detail and they’ve discovered so much about music. But they don’t know exactly what some of the things mean. Hopefully, I’ll be able to contribute to this someday.

Soundtrack: Jazz Violin (Album Smooth Jazz Strings)

Disclaimer: These are book thoughts on The Music Instinct (2010) by Philip Ball. The content is the author’s intellectual property.